Nez Perce Nation |

Nez Perce Nation Flag |

Origin of the NameThe name "Nez Perce" comes from the French phrase meaning "pierced nose." Early French explorers and fur traders gave the tribe this name after encountering some neighboring groups with nose piercings. However, the Nez Perce themselves traditionally did not practice nose piercing. They call themselves Nimiipuu, meaning "the people," which reflects their deep sense of community and identity. RangeThe Nez Perce traditionally lived in the Plateau region of the Pacific Northwest, with territory covering parts of present-day Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Montana. Their homeland stretched along the Clearwater, Snake, and Salmon Rivers, with access to the rich fishing areas of the Columbia River. Seasonal movement was important: they wintered in sheltered river valleys, fished and gathered roots in spring, and traveled eastward onto the Great Plains for buffalo hunts in summer. DietThe Nez Perce diet reflected the diversity of their homelands. Salmon was the staple, caught in huge quantities during the annual runs and dried for winter storage. They hunted deer, elk, mountain sheep, and, after acquiring horses in the 1700s, joined buffalo hunts on the plains. Plant foods such as camas bulbs, bitterroot, and huckleberries were gathered in abundance, often baked in earth ovens or dried into cakes. These foods carried not only nutritional value but also spiritual meaning—camas was considered a sacred gift of the Creator. Home TypeThe Nez Perce built different types of homes depending on the season. In winter, they lived in large semi-subterranean earth lodges covered with layers of soil and grasses, which kept warmth inside. In warmer months or on buffalo hunts, they stayed in tipis made of wooden poles and buffalo hides, which were portable and ideal for travel. These flexible housing styles reflected their adaptability to different environments. CultureThe Nez Perce developed a vibrant cultural life that combined spirituality, artistry, and deep ties to the natural world. After acquiring horses around 1700, they became expert riders and breeders, producing the famous Appaloosa horse. The spotted Appaloosas were not only strong and swift but also a source of tribal pride, often decorated with paint, beads, and feathers.

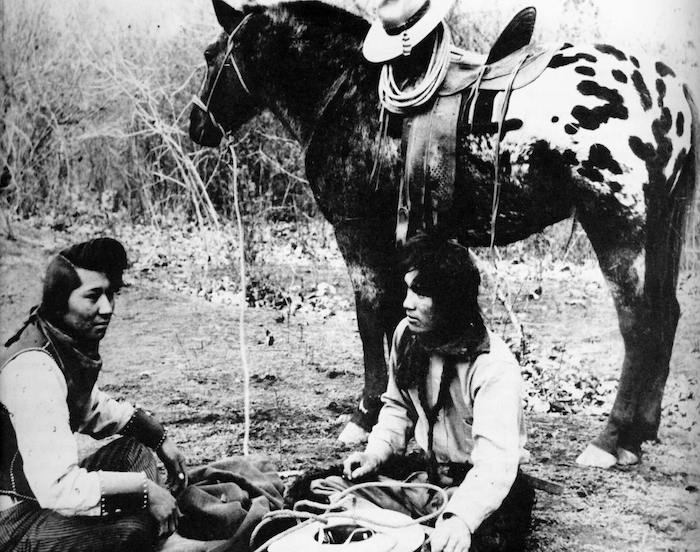

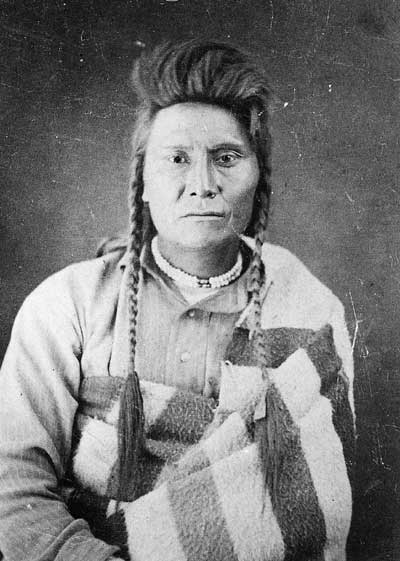

Nez Perce with an Appaloosa Horse (c. 1895) Spiritual beliefs centered on a living world filled with powerful spirits. Children and young adults often went on vision quests, fasting and praying alone in the wilderness to gain guardian spirits who would protect and guide them. Ceremonies such as the First Salmon Feast honored the return of salmon each spring, with rituals to thank the spirits of the fish for sustaining the people. This ensured balance between humans and nature. The Nez Perce also carried a rich body of myths. One well-known story tells of Coyote, the trickster and cultural hero, who shaped the land and rivers. According to legend, Coyote killed a great monster that had swallowed all the animals. Cutting the monster’s body into pieces, he scattered them across the land, creating the different tribes. He left the Nez Perce in their homeland, giving them responsibility for the rivers and salmon. Such stories explained not only the world’s creation but also the Nez Perce’s role within it. WeyekinsAmong the Nez Perce, a weyekin (sometimes spelled wyakin) is a personal spirit guardian that provides strength, guidance, and protection throughout life. Young people traditionally sought their weyekin during a vision quest, a rite of passage that involved fasting, solitude, and prayer in the wilderness. The spirit might reveal itself through an animal, a natural force, or a dream, and once gained, it remained a lifelong helper. The weyekin was deeply personal—it was not worshiped but respected as a sacred companion linking the individual to the spirit world. This practice reflected the Nez Perce belief that all of nature was alive with power and that humans lived in constant relationship with the spiritual forces around them. WarfareThe Nez Perce were generally peaceful but defended their lands fiercely when threatened. Traditionally, they fought with bows, arrows, war clubs, and later rifles. They painted their horses and faces with symbolic designs before battle. In the 19th century, as settlers encroached on their homelands, they became skilled guerrilla fighters, using knowledge of rivers, mountains, and valleys to outmaneuver U.S. soldiers. The Nez Perce War of 1877 is the most famous chapter of their military history. It began after the U.S. government attempted to force all Nez Perce onto a reservation in Idaho. Led by leaders like Chief Joseph, Looking Glass, and White Bird, around 750 Nez Perce men, women, and children embarked on a 1,200-mile retreat through Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, fighting several battles against pursuing U.S. forces. Despite winning tactical victories, they were eventually surrounded in the Bear Paw Mountains, just 40 miles from the Canadian border. Chief Joseph’s surrender speech—“I will fight no more forever”—remains one of the most famous in Native American history.

Chief Joseph History Timeline

Discussion Questions

The Nez Perce PeopleThe Nez Perce are a Native American tribe who lived for thousands of years in the Pacific Northwest. Their homeland covered parts of present-day Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. They lived in villages along rivers, where they fished for salmon, hunted game, and gathered plants. Horses, which they began using in the 1700s, became very important for travel, hunting, and trade. Early Contact with EuropeansThe first Europeans to meet the Nez Perce were members of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1805. The tribe helped the explorers survive the difficult journey by giving them food and guidance. After this, traders and settlers began to enter Nez Perce lands. While the tribe often traded with newcomers, settlers’ demands for land grew over time. Conflicts and the Nez Perce WarIn the mid-1800s, the U.S. government forced the Nez Perce to give up most of their land through treaties. Some groups agreed, but others refused. In 1877, conflicts broke out when the U.S. Army tried to move resistant bands to a reservation. This began the Nez Perce War, during which Chief Joseph and his followers traveled over 1,000 miles in an attempt to reach safety in Canada. They fought several battles but were eventually forced to surrender just short of the border. Life After the WarAfter their defeat, the Nez Perce were sent to reservations far from their homeland. Conditions were harsh, and many people suffered. Over time, some were allowed to return to Idaho, while others remained in Washington and Oregon. Today, the Nez Perce continue to preserve their culture, language, and traditions while also participating in modern American life. |